The following is Bathsheba W. Smith’s record of crossing the Plains. You will see that this was a woman used to the finer things in life; yet, she too had to face the hardships of the trek across the Plains. We often don’t realize that most of the pioneers were city-folk roughing it for the first time on some long-winded camping trip. The only thing that kept them going was their sure testimony of living the religion they so faithfully adopted.

was a woman used to the finer things in life; yet, she too had to face the hardships of the trek across the Plains. We often don’t realize that most of the pioneers were city-folk roughing it for the first time on some long-winded camping trip. The only thing that kept them going was their sure testimony of living the religion they so faithfully adopted.

As soon as the weather became warm, and the gardens began to produce early vegetables, the sick began to recover. We felt considerable anxiety for the safety of the pioneers, and for their success in finding us a home. About the first of December, to our great joy, a number of them returned. They had found a place in the heart of the Great Basin, beyond the Rocky Mountains, so barren, dry, desolate and isolated that we thought even the cupidity of religious bigots would not be excited by it. The pioneers had laid out a city, and had commenced a fort and some seven hundred wagons and about two thousand of our people had by this time arrived there. The country was so very dry that nothing could be made to grow without irrigation.

After the location of Winter Quarters, a great number of our people made encampments on the east side of the river, on parts of the Pottawatomie lands. The camps, thus scattered, spread over a large tract. On one occasion my husband (George A. Smith) and I visited Hyde Park, one of these settlements, in company with the twelve apostles. They there held a council in a log cabin, and a great manifestation of the Holy Spirit was poured out upon those present. At this council it was unanimously decided to organize the First Presidency of the Church according to the pattern laid down in the Book of Covenants. Soon after, a general conference was held in the log

tabernacle at Kanesville (now Council Bluffs), at which the saints acknowledged Brigham Young, President of the Church, and Heber C. Kimball and Willard Richards his councilors. Shortly after this conference our family moved to the Iowa side of the river. My husband bought two log cabins, and built two more, which made us quite comfortable. The winter was very cold, but wood was plentiful, and we used it freely. The situation was a romantic one, surrounded as we were on three sides by hills. We were favored with an abundance of wild plums and raspberries. We called the place Car-bun-ca, after an Indian brave who had been buried there.

In May 1848, about five hundred wagons followed President Young on his return to Salt Lake. In June some two hundred wagons followed Dr. Willard Richards. When Dr. Richards left, all the saints that could not go with him were compelled by the United States authorities to vacate Winter Quarters. They recrossed into Iowa, and had to build cabins again. This was a piece of oppression which was needless and ill-timed, as many of the families which had to move were those of the men who had gone in the Mormon Battalion. This compulsory move was prompted by the same spirit of persecution that had caused the murder of so many of our people, and had forced us all to leave our homes and go into the wilderness.

On the Iowa side of the river we raised wheat, Indian corn, buckwheat, potatoes, and other vegetables; and we gathered from the woods hazel and hickory nuts, white and black walnuts, and in addition to the wild plums and raspberries before mentioned, we gathered elderberries, and made elderberry and raspberry wine. We also preserved plums and berries. By these supplies we were better furnished than we had been since leaving our homes. The vegetables and fruits caused the scurvy to pretty much disappear.

In September, 1848, a conference was held in a grove on Mosquito Creek, about two thousand of the saints being present. Oliver Cowdery, one of the witnesses of the Book of Mormon, was there. He had been ten years away from the Church, and had become a lawyer of some prominence in Northern Ohio and Wisconsin. At this conference I heard him bear his testimony to the truth of the Book of Mormon, in the same manner as is recorded in the testimony of the three witnesses in that book.

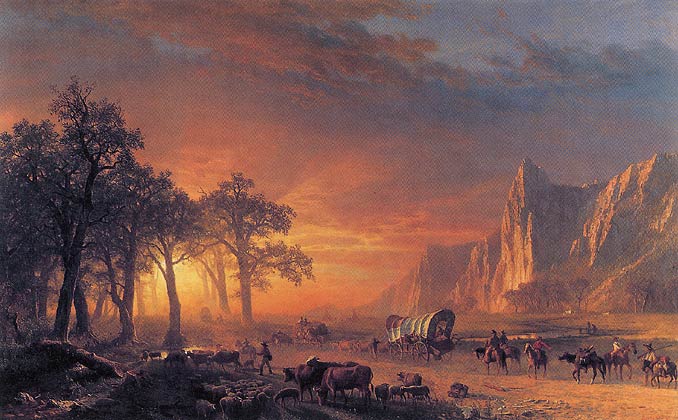

In May 1849, about four hundred wagons were organized and started West. In the latter part of June following, our family left our encampment. We started on our journey to the valley in a company of two hundred and eighteen wagons. These were organized into three companies, which were subdivided into companies often, each company properly officered. Each company also had its blacksmith and wagonmaker, equipped with proper tools for attending to their work of setting tires, shoeing animals, and repairing wagons.

Twenty-four of the wagons of our company belonged to the Welch saints, who had been led from Wales by Elder Dan Jones. They did not understand driving oxen. It was very amusing to see them yoke their cattle; two would have an animal by the horns, one by the tail, and one or two others would do their best to put on the yoke, whilst the apparently astonished ox, not at all enlightened by the gutteral sounds of the Welch tongue, seemed perfectly at a loss what to do, or to know what was wanted of him. But these saints amply made up for their lack of skill in driving cattle by their excellent singing, which afforded us great assistance in our public meetings, and helped to enliven our evenings.

On this journey my wagon was provided with projections, of about eight inches wide, on each side of the top of the box. The cover, which was high enough for us to stand erect, was widened by these projections. A frame was laid across the “back part of our wagon, and was corded as a bedstead; this made our sleeping very comfortable. Under our beds we stowed our heaviest articles, We had a door in one side of the wagon cover, and on the opposite side a window. A step-ladder was used to ascend to our door, which was between the wheels. Our cover was of Osnaburg, lined with blue drilling. Our door and window could be opened and closed at pleasure. I had, hanging up on the inside, a looking-glass, candlestick, pincushion, etc. In the centre of our wagon we had room for four chairs, in which we and our two children sat and rode when we chose. The floor of our traveling house was carpeted, and we made ourselves as comfortable as we could under the circumstances.

After having experienced the common vicissitudes of that strange journey, having encountered terrible storms and endured extreme hardships, we arrived at our destination on the 5th of November, one hundred and five days after leaving the Missouri River. Having been homeless and wandering up to this time, I was prepared to appreciate a home.

This record can be found in Women of Mormondom, by Edward Tullidge.